Elisabeth Frink

Dame Elisabeth Frink RA (1930-1993)

BRONZE ATLAS MAQUETTE

Signed and numbered 1/9

Conceived in 1983

Measurements: 26" (63.5 cm) High

Together with:

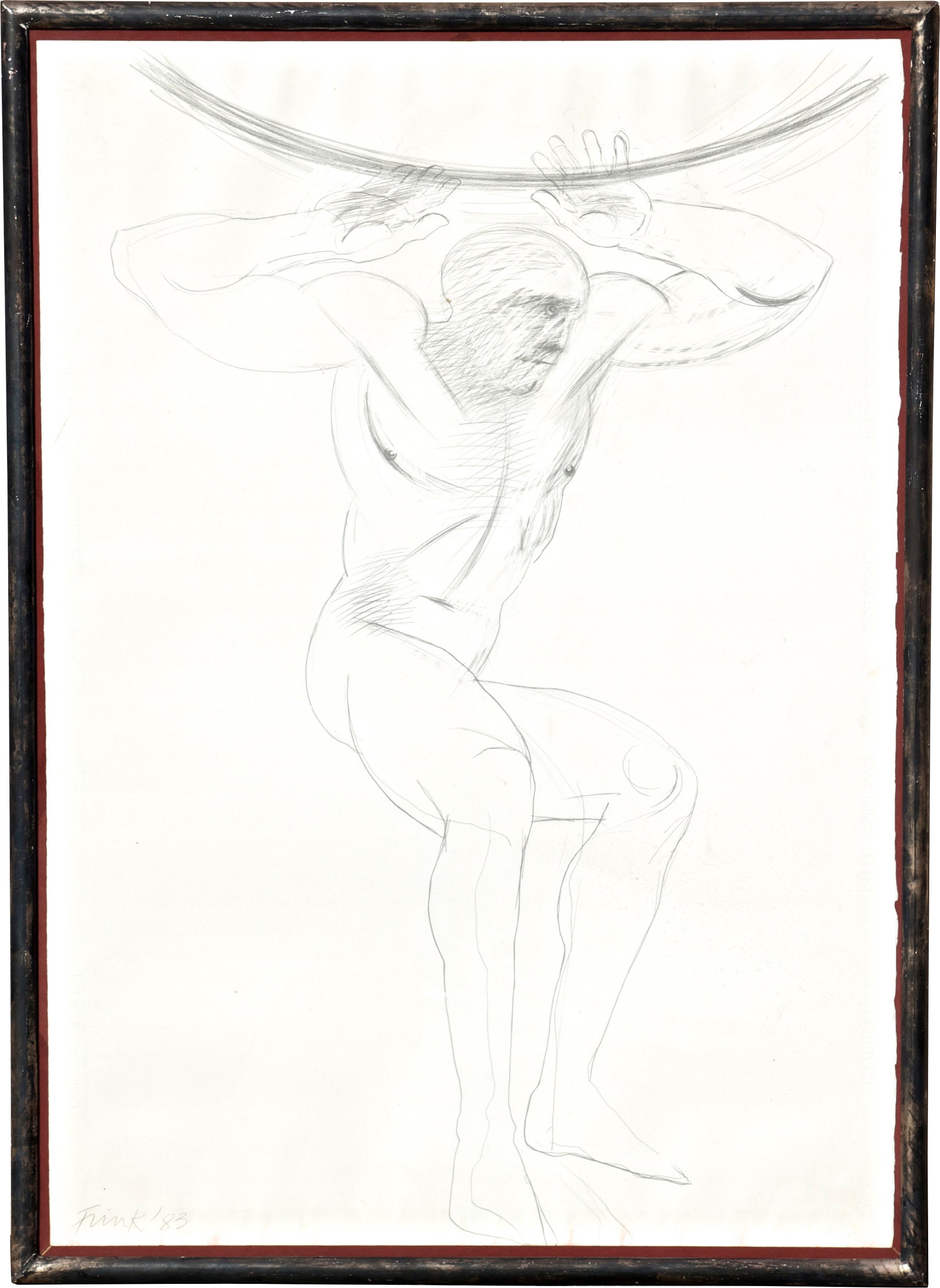

A SUBSTANTIAL FRAMED PENCIL STUDY FOR THE ATLAS MAQUETTE

Signed and dated 1983

Measurements: 39” x 27” (100 x 70 cm) unframed; 41 ¾” x 30” (106 x 76 cm) framed

Provenance: Acquired from Bobby & Virginia Chapman, Debden Manor, near Saffron Walden, Essex.

Literature: Edward Lucie-Smith, Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture since 1984 and Drawings, Art Books International: London, 1994, Cat. No. SC0b.

The striding figure in bronze with a rich brown patination, presented on an integrated base and supporting an open framework suggestive of the globe. Together with a framed original study for the work, inscribed “Frink ‘83”.

This bronze maquette relates to a one and a half times life-size figure of Atlas, 1983, now in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. The work was originally commissioned by Bobby Chapman, the project architect, on behalf of Commercial Union Properties to stand outside their new headquarters at Crutched Friary in the City of London. The building, known as Friary Court, was designed by Chapman Taylor Partners: the firm co-founded in 1959 by Bobby Chapman, the former owner of the present works. One of London’s leading architectural firms, Chapman Taylor Partners also completed projects for the Crown, Grosvenor and Cadogan Estates.

Bobby Chapman was a great advocate of fusing architecture and sculpture, and through his firm patronised a number of prominent sculptors, including Elisabeth Frink and William Pye. It was Chapman who commissioned Frink’s Horse & Rider, 1974, the only public sculpture on London’s Piccadilly, and who later recommended her for the Commercial Union project.

The Atlas was conceived as the imposing frontispiece to the daring new development at Crutched Friars. The Classical subject was inspired in part by archaeological excavations at the site, which revealed, among other items, two ceramic figurines of Venus and Mercury, dating back to the Roman era. According to Greek mythology, Atlas was the Titan condemned by Zeus to support the celestial sphere as punishment for his role in the Titan uprising. His muscular form, straining under the weight of the heavens, was a popular theme with sculptors from antiquity onwards, gaining particular momentum during the Renaissance.

Here, however, Frink has not adopted the motif wholesale, but rather imbued it with her own personal mythology. Throughout her career, Frink was drawn to the male form, using it as a means to explore her own vision of masculinity – at once heroic, fragile and brutal. This preoccupation has often been linked to her childhood spent in Suffolk in the shadow of the Second World War, pining for her absent soldier father. Her family home was surrounded by RAF air bases, and Frink was also fascinated by the bravery of the dashing young airmen whose lives were all too frequently cut short. Following the war, her belief in the fundamental heroism of men was shattered by the images of desolation that came out of the Nazi camps – proof that man was not always governed by the rules of the officers’ mess, but could descend into inhuman brutality.

Frink’s Atlas, then, is not a symbol of immovable strength, but a reflection of humanity’s fragility. The tall, muscular frame strides forward with determination and resilience, but the melancholy expression betrays an inner turmoil. This conflict is emphasized by the uneven texture, created through Frink’s unique method of casting in smooth plaster and then cutting and carving at the surface to create a loose, tumultuous finish. Here, these deep cuts take on the appearance of scars, particularly across the back and upper torso, where they have been used to define the musculature. Such scarring recalls her preoccupation with the damaged psyche of the soldier – Atlas was, after all, atoning for his part in the battle between the Titans and the Olympian gods. At the time, post-traumatic stress disorder was a relatively new concept as the idea only emerged in the popular consciousness during the 1970s, in response to the Vietnam War. Frink, however, had long been acutely aware of the long-term physical and psychological damage of war; her second husband was Edward Pool, a D-Day veteran who had lost a leg in battle.

Accompanying the bronze, we also present a preparatory sketch for the Atlas commission, signed by Frink and dated ’83. The sketch shares the bronze figure’s emphasis on the upper musculature, with the main definition of the torso conveyed through deep cuts to the surface of the bronze, and heavy, scrubbed-in lines in pencil on the drawing. Although the sketch simplifies the form, pushing it towards graphic abstraction, Frink has shaded the face heavily, predicating both the rugged texture, and sombre melancholy of the bronze maquette. In contrast, the lower half of the figure is quite different in the preparatory drawing. Rather than the solid, striding pose of the maquette, Frink has drawn the legs in a squat position, emphasizing the physical strain of the stance but also creating a visual instability lacking in the bronze.

Collections: Antiques, Latest Pieces, Sculpture & Objects

Share: